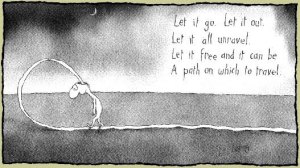

Ellen had never been what you would call artistic. She’d never been able to make the picture in her head come out the right way; the images instead teensy and wonky and just sort of curious – a travesty of what she had wanted. A teacher had told her once that she had no poetry in her soul and she hadn’t even been offended. Words, she understood in a way she never could a picture or, if she were honest with herself, a glance or a touch; such tiny actions which rendered her – Ellen Michaels – speechless. Words were something solid, something dependable and you always knew where you stood with words.

Then the plane touched down on the tarmac at Sydney International, and Dave was beside her, outlined against the beyond blue sky in the tiny window. Dave had grabbed her hand suddenly, painfully, and his hand was sweaty against hers but she didn’t mind because her stomach was twisting and jolting in a way that should have been unpleasant but she might be about to meet her birth mother and –

She had no words. They should have sent a poet.

*

Ellen had thought Australia would be hot, even during the winter. She had thought she wouldn’t need a coat or a scarf here; that her lips wouldn’t be chapped from the wind and that she wouldn’t have to apply moisturiser to dry cracked hands in the morning, rifling carefully through her bag in the semi-darkness of the hotel room so as not to wake Dave. He tended to drift off at odd times, like when they were on the bus or in yet another waiting room or once, sitting in a grimy booth at McDonald’s that to Ellen just felt dirty. She stared at his dark head on the pillow next to her, thinking about how different things had been since his brother had died.

At first, they had touched a lot. They had even kissed once, at the wake. She had paused at his door, listening for any noise. Suddenly Dave was in front of her. She had been pushed roughly up against the door, black dress against black suit and hands slammed above her head. Heart hammering in her chest she had seen something in his eyes that scared her, because she wasn’t sure if she could fix something so broken and the thought that Dave might never be the same again was too awful to contemplate. Dave had grunted and crashed his lips to hers and Ellen had had to remind herself that this was Dave, her Dave, and he wouldn’t hurt her, ever, not in that way. So she had closed her eyes and kissed him back, because he was still Dave and she wanted to yell at herself because she was only eighteen and shouldn’t be thinking things like oh God, this is it, forever at her age. Maybe, though, with one of Dave’s hands tangled in her hair and the press of him along the line of her body, there was hope for them and she shivered at the idea.

Perhaps Dave had felt the tremor run through her because he had broken off suddenly and pressed his forehead against hers for a moment, eyes closed and shoulders heaving, gradually loosening his grip on her wrists. She brought her hands down slowly, the way you would with an animal that has been cornered, no sudden movements. The grip marks on her wrists were red and angry against her skin and she rubbed vaguely at the marks. Dave had opened his eyes then.

“Did I do that?” His voice was thick and heavy, and if Ellen had been a meaner person she would have looked to see if he was crying, but she didn’t. Instead, she pulled the sleeves of her cardigan over the marks, shrugging.

“It’s fine. You didn’t mean to.”

“I’m-” Dave’s voice broke, and Ellen reached a hand up to his face suddenly. He started at the movement, and she caught a glimpse of his anguished expression before he tore himself away. She pressed against the door as she listened to his heavy footsteps down the stairs.

They hadn’t spoken about it since.

She had thought that Dave needed to be somewhere different where his siblings weren’t walking around like ghosts and his mother didn’t burst into tears at the sight of a pair of Jack’s socks; somewhere his father’s mouth wasn’t a perpetual grim line. He had offered to go with her to find her mother, one hand rubbing the back of his neck awkwardly while trying not to look as though he was saying something important. She had wondered whether this had anything to do with the kiss, but then he had cleared his throat and she had looked up to find his eyes on her, and that had been that. She had nodded, and he had nodded, and they left a week later.

She had thought that they would be okay here in Australia; that they would be a they here, not a him and a her, but the hotel air between them was filled with awkward space she couldn’t breach. Watching him sleep was all she had and it wasn’t enough and she shouldn’t even be thinking about this while she had a job to do.

Over the next few days, they continued to search, grabbing phone books and business directories from hotel concierges who spoke something that sounded like English but wasn’t really, and they would emerge from the lobby, blinking in the bright light that was bright in a way that was different to how it was in England.

Ellen imagined that when she met her mother, she would pat her on the head and tell her it was just culture shock, but her mother was sort of the problem. Ellen didn’t know where she was.

*

“We’re going to Brisbane.”

Dave’s head snapped up from his study of the remote control and he nodded slowly.

“Okay." There was a silence, then, “Do you want to play a game?”

Dave’s eyes met hers and she swallowed. “What sort of game?”

“Well,” Dave began, “It’s meant to be played with alcohol.”

Ellen shifted against the door, and Dave’s eyes followed the line of her legs up to her thighs. Ellen tried not to look at the way his hands clenched slightly, skin pulling taught over thick fingers and veins standing out for a moment. It’s just a hand, you idiot, she told herself.

“It’s called, ‘I never’, and you have to start off a sentence with ‘I never’ and then follow it with something you’ve never done, and if the other person has done it they drink.”

Ellen nodded slowly as Dave rummaged in the bar fridge, muttering to himself.

“I know there’s some in here somewhere.”

He looked up at her with a smile on his face, bottle in hand.

“Ready?”

*

“I’ve never failed a subject in my life,” Dave nudged her with his shoulder; head tipped toward hers as he took a swig. Ellen wanted to tell him that he was missing the point of the game; that he was meant to say things he hadn’t done, but he winked at her like he knew what she was thinking and she giggled. They lay next to each other, shoulders touching. A tiny part of her was horrified at the fact that she was brave enough to try to chase down her birth mother but still couldn’t tell Dave she was half in love with him, so she told him something else instead.

“I failed art.” Ellen screwed her eyes shut. She felt Dave shift beside her and cracked an eye open. He quirked his eyebrow at her.

“You failed it? Actually failed?”

Ellen nodded, flushing red.

“Yes.”

“Wow.”

“I’m just not creative. It’s fine, I’ve never really been bothered by it. Once actually, a teacher looked at this picture I had drawn of my adopted family and just about fell to the ground laughing. I was ten.”

“That’s horrible! What a useless bloody teacher.”

She shrugged, “Not really. It was a rather dreadful painting.”

“But still, I mean, it’s not as though – she could’ve been nicer about it couldn’t she?”

Dave looked so adorably put out that Ellen wanted to hug him. So she did. He stiffened slightly before Ellen decided that enough was enough.

“Just hold me,” she mumbled into his shirt, just quietly enough so that if he wanted to he could pretend not to have heard it, but then he put his arms around her. The tightness in her stomach receded and she breathed him in.

“Imagine if I hadn’t run away from you last time,” Dave said suddenly into the stillness, anger underlying his voice as he gulped his drink.

“I would’ve…I would’ve kissed you a lot sooner.” The air was filled with a pleasant tension that sizzled and popped between them, and maybe it was the alcohol but Ellen felt something swelling inside her, like if air was a feeling.

“If I let you, you mean,” she teased, nudging him with her shoulder.

“Let me?” Dave said, mock offended. “Please, you were begging for it.” There was a beat, then, “I would have wanted to.” Dave’s voice was barely above a whisper and Ellen could feel the warm vibration shift the loose strands of hair around her ear. She looked up at him then, and her breath caught because in that moment, in that hotel room in Sydney with the noise of passing traffic muffled on the street below them, she could forget, for a tiny moment, about why she was there and focus instead on the person she came there with.

“I had fun tonight. I mean, despite everything, this is the most fun I’ve had in ages.” Ellen’s voice was breathless and a slow smile spread over Dave’s face.

“Yeah. Me too.” His voice was thick and low; it made Ellen shiver a little bit. He reached out an arm towards her, tucking a strand of hair behind her ear.

“Thank you,” he said seriously.

“For what?”

“For just…you know. Being there. For everything. For letting me come with you. These past few weeks have been bloody awful, but you’ve made it…you know…bearable.”

“So have you,” she said. “I couldn’t have done this without you.”

Her stared at her and she swallowed noisily.

“It’s funny,” Dave said. “It changes you,” and Ellen didn’t have to ask what he was talking about. She could hear it in his voice, the slight ache that always came when he spoke about his brother Jack.

“Maybe not in a huge noticeable way, but it does change you. You look at things a bit differently, and you feel,” Dave hesitated for a moment, shrugging, searching for the right words. “I dunno, you feel sadder, I guess, and older, but not necessarily wiser,” he smiled ruefully as he said this and looked at her sideways.

“I’m going to be there for you, you know,” Ellen said suddenly. “No matter what.”

Dave was silent for a moment, just staring at her. Then, without warning, he leaned closer, trailing one hand along the side of her face till he was cupping her chin.

“Ellen. I think you’re bloody brilliant,” he said, and then his lips were on hers, and Ellen’s arms found their way around his neck. It was all softness and slow, warm motion and Ellen sunk down deeper into him, until she couldn’t remember what it was like to not kiss Dave, to not be with him like this. He tasted like heat and alcohol and smelled so familiar that she felt an ache well up inside her at the thought that finally, finally, things were making sense. She was going to meet her mother and she would be with Dave.

*

Ellen hadn’t expected Brisbane to be beautiful, but after spending two days walking around the city squinting in the harsh winter sunlight that didn’t seem to warm anything up, she had gotten used to the light and the space and the winding river that ran through it all. It reminded her a little of a smaller, quieter London, but this time it didn’t make her homesick. With Dave next to her, occasionally holding her hand and rubbing his thumb against hers, she thought that maybe they could one day come back for a visit; a proper visit, with cameras and dorky clothes and they would smile and laugh more. They wouldn’t have a job to do.

“Here we are,” Ellen said, peering up at the tiny numbers over the doorway.

“I’ve got a good feeling about this one,” Dave said and Ellen smiled. He said that every time.

“What’s this now? Seventeenth time lucky?”

“You never know.”

*

It was her mum’s voice that did it. Ellen had waited anxiously for her knock to be answered, and it was, and her mother had known who she was, and she had said, “Hello”, as though it was something they had said to each other every single day.

There was a silence for a while, during which Ellen just stared at her mother, drinking her in, and she so badly wanted to hug her and have her mother tell her that everything was okay and stroke her hair and make her some cocoa and talk to her about the Dave situation and her mother would be happy for her, but –

She didn’t have the words.

*

The introductions were a tiny bit awkward. Dave had tried very hard to look as though he hadn’t spent the last week or so sleeping in the same bed as her daughter. He had kissed Ellen’s mum’s cheek and then tactfully disappeared, saying he would meet up with her at the hotel.

*

Ellen was waiting in the lobby when Dave finally returned. She heard a cough behind her and spun around and saw Dave standing there with a small package in his hands. She took it confusedly.

“What’s this for?”

“Just open it.”

A small box fell out, with the words ‘digital camera’ printed on the side. Ellen stared at the box for a while, dumbfounded.

“Well, are you going to say anything?"

Ellen looked up at him, and the expression on her face must have reassured him somehow because he visibly relaxed, the tension fading from the lines of his shoulders as he breathed a sigh of relief.

“So do you like it? You do like it don’t you?”

“I-” Ellen said. She didn’t think ‘like it’ were the right words here. Maybe, love-it-so-much-you-are-so-brilliant-I-want-to-be-the-mother-of-your-children, might have been going a bit far, but she didn’t think so.

“I know you don’t think you’re artistic, and all that,” Dave continued, “but I think that you should, you know,” he stopped, brow furrowing as he thought about what he was trying to say. “You have things in your life that you should make memories of, you know? Good things, things that you’ll want to look back on and be like, yeah, that was bloody brilliant, and it doesn’t matter if everything comes out blurry, you shouldn’t let that stop you.” He took a deep breath and slipped his thumb along her jaw.

“Because you’ll want something like that at some point. I wish-” he broke off, staring at her for a minute. “Well, I had to use Jack’s money for something, right?”

Suddenly, telling Dave she wanted to be the mother of his children didn’t seem to be a big enough gesture, but she thought that with Dave, she might have to start small.

“Thank you,” she said, trying to convey in those two words exactly how grateful she was to him. Dave nodded and she decided she didn’t care that they were in a hotel lobby. Today, she had met her mother and it was all because of him. She threw her arms around him and kissed him then, before she could change her mind. Dave did this thing with his hand where he traced a small circle on her back and nothing mattered except the feeling of him against her and the fluttering in her stomach and the beat of his heart and she didn’t want to stop. Ever. She somehow thought that Dave wouldn’t mind.

*

Ellen wrote to her mother every fortnight after returning home, and Ellen visited her again many times. Ellen always took two things with her: Dave, and her camera.